Article on Early English Chess Sets

Focused on the design and evolution of the pieces form

What did 16th Century English chess sets look like?

Dermot Rochford

What evidence from the 16th century is available?

To answer this question the obvious starting point is to look at the two pieces of evidence we have that actually originate from the 16th Century. These are;

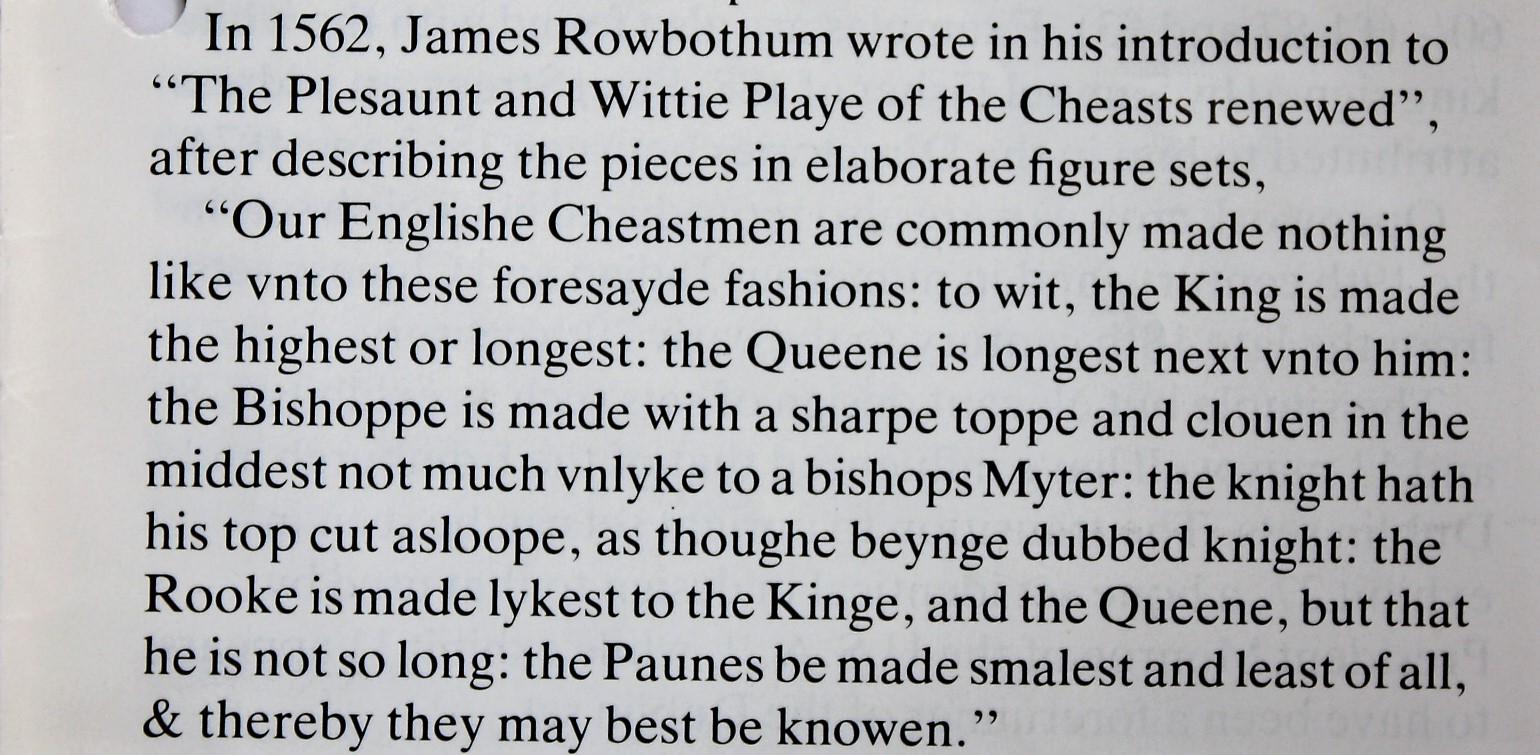

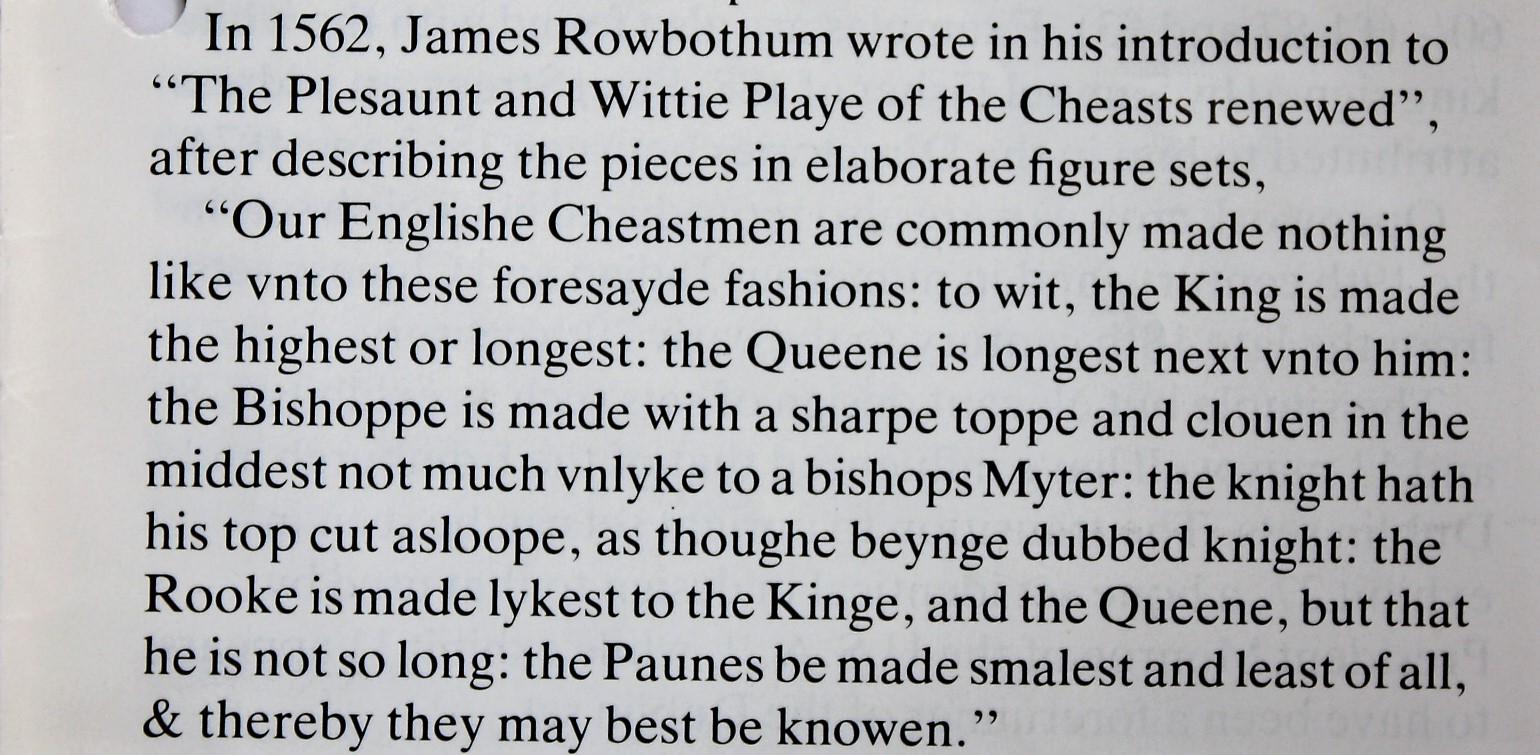

(a) The Rowbotham Description (From Michael Mark’s booklet)

Most chess collectors who have read Michael Mark's booklet on British Chess Sets (1986) will have seen (but possibly, like me, not paid too much attention to it) his reference to a 16thC. book entitled;

'The Plesaunt and Wittie Playe of the Cheasts renewed' written by James Rowbotham and published in 1562, in which he describes the typical English playing chess set of the time as follows;

Figure 1

So from that account it would appear that the kings, queens, rooks and pawns were similar to each other and were mainly distinguished from each other by size/length of each chess piece. Rowbotham does not tell us if there were any other features associated with these 4 pieces which might help distinguish a king from a queen or a rook (e.g. a crown), so we can probably assume that these pieces all had the same type of tops (i.e. ball finials). Rowbotham does provide some specific design information in respect of 2 pieces, the bishops, which were identified by a bishop's mitre, and the knights, as cut aslope front top (rather than a horse’s head).

However we are left totally in the dark about the design and complexity of the turning associated with the bases and stems of all the pieces or indeed the actual size of the chess pieces.

We don’t know it for certain but it is possible to speculate that by the manner of his description, Rowbotham was referring to a chess set design which was in general use at that time, at least in the capital, London..

(b) Windsor Family Painting

In his commentary in the booklet, Michael Mark does draw our attention, to the image on the front cover, of a 1568 English oil painting showing the family of Lord Windsor playing chess. In so far, as it is possible to discern, many of the 18 pieces on the chess board could fit the general Rowbotham description – see Figure 2 below.

Figure 2

As far as I can see the pieces shown on the chessboard include one multi knopped king with ball finial, two smaller double knopped pieces (queens?) with ball finials, a knight with a large slope front cut and many pawns with large baluster knop stems surmounted by collars and plain ball finials. It is not possible to see clearly if a bishop or rook is present.

So while it certainly seems plausible to suggest that the chess set in the painting generally fits the Rowbotham description, the fact that the Rowbotham description is vague as to the format of most of the chess pieces described and the Windsor painting does not show all the relevant chess pieces and also is indistinct with regard to the turning style of the stems (other than the pawns), makes it difficult to make any confident assertion that the two sets are of the same design.

17th Century Sources

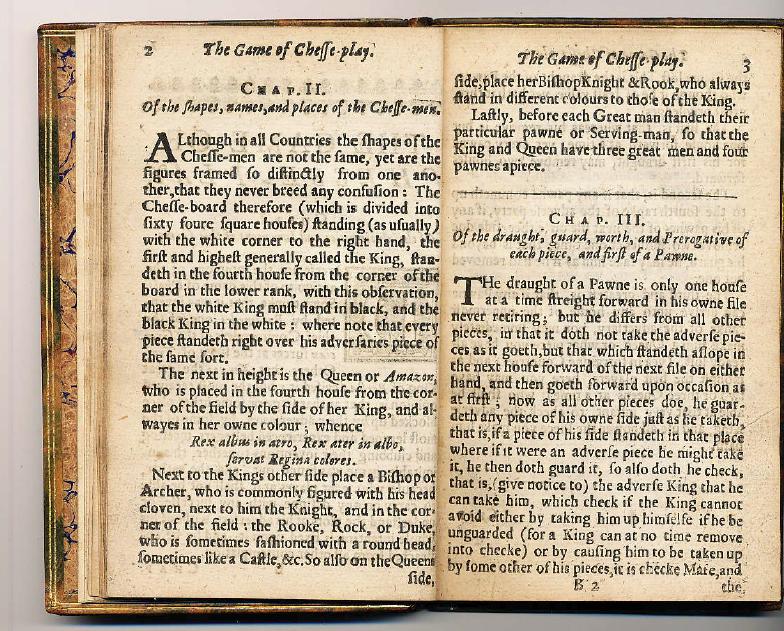

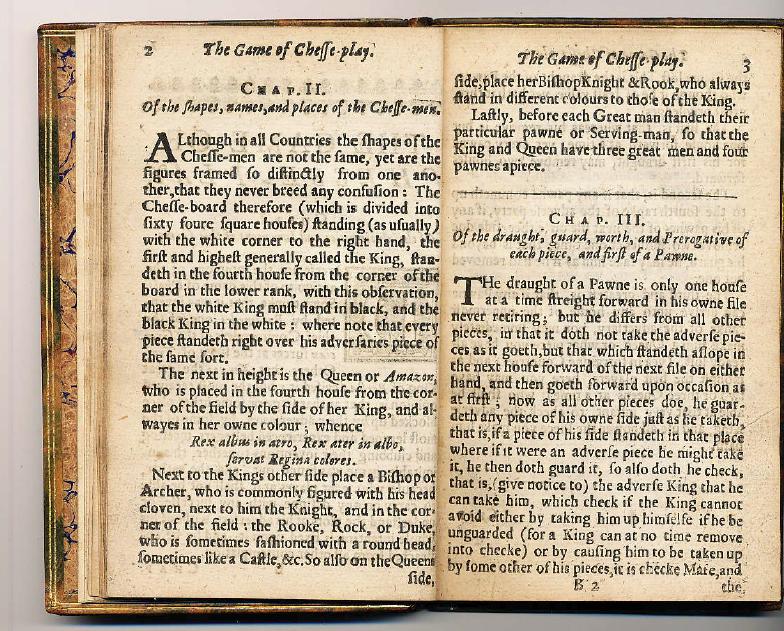

In Francis Beale’s 1656 translation of Greco, it is stated that the rooks ‘sometimes fashioned like a round head and sometimes like a castle’ (see Figure 3 below).

Figure 3

This supports the Rowbotham description of a 16th century English rook being similar in design to a king or queen rather than a conventional castle. In this regard Michael Mark observes that the rook only gradually transposed into a castle in the course of the 17th century and the transposition may not have been complete until the 18th century.

Making comparisons to known 18thC Chess sets.

Up to recent times we had little else to go on other than the option of examining extant 18th century sets and to speculate how near or far the design of the sets were from 16t century sets. Given the likelihood that the Rowbotham/Windsor type set was probably used for a century or two after the 16th century publication and painting, it is quite reasonable to look at. say early 18th century sets for possible evidence of the 16th century chessmen design.

One such chess set is an 18th century ivory and horn set shown in Michael Mark's Chessmen – Practical and Ornamental booklet, under Exhibit 1. Below is an image (Figure 4) of similar example I have of this early English set.

Figure 4

From a chess set design point of view, it appears to have a number of features of the Rowbotham/Windsor sets, with its multi-knopped kings and queens and knights 'cut aslope' and in dimensions it is small and squat rather than tall and slender. However, it obviously differs in that the king does not have a ball finial but is topped by a ‘cushioned’ crown and the rook Is an early type castle with its tapering cylindrical body.

So while Exhibit 4 may provide some assistance in imaging what the Rowbotham set looked like, it clearly is not the full answer.

Recent Finds

In the last couple of years some early English sets with more distinct ‘Rowbotham’ features have come into the public arena.

First of all, fellow collector and author Sir Alan Fersht outbid me on Ebay for what appeared to be an incomplete, early English ivory chess set but with spare queens from a similar but smaller set and some 19th century Calvert type rooks.

It led to a discussion during which Alan told me, Michael Mark had drawn his attention to the Rowbotham description of the rook being a smaller version of the king and queen - so in fact the 'spare queens' were rooks of the ‘Rowbotham’ style and an integral part of the chess set he had acquired. See image Figure 5 below.

Figure 5

So, this was an important find because, as far as I am aware, prior to this, we had not seen in public an early English set with these type of ‘Rowbotham’ rooks.

While it seems certain that this set is at least 18th century (and could be earlier) the intriguing question is how closely might it match the 'Rowbotham/Windsor' set. Clearly Alan's set is multi-knopped, with ball finials (except for the king), has the right knight form and crucially the correct rook form. The more ‘waisted’ format of the stem structure of the pawns appears to differ from the more bulbous stems of the pawns in the Windsor painting.

Then in early 2017, I was offered an early wood English type set (which had been found in an antique shop in the South West of England) - this set was fairly similar to Alan's set in general design and height (K.8cms) but with some differences in the turning on bases and stems and the kings had plain ball finials rather than cogged crowns - see image Figure 6 below.

Figure 6 (also P153 on our website)

This set is also at least 18th century and appears to be a more sophisticated version of the ivory/horn set in Figure 4 as can be seen by the variety of designs in the bases, inverted ringed baluster stems, knops, tiered grooving and collar construction. Also, the image shows how the upper structures of the kings, queens, rooks and pawns are very like each other and the pieces are differentiated mainly by the vary heights of each piece, a feature that is in line with the Rowbotham description of these pieces. This certainly adds weight to the case that this type of design/style of chess set could be very like that used in the 16th century.

A fuller description of this set’s design features is available in Addendum A at the end of this article.

Two other examples are worth mentioning;

One is a set currently on Luke Honey’s site; www.lukehoney.co.uk, and described as 17thC. – see Figure 7 below;

Figure 7

The other is an ivory set (natural and black stained) which I bought in Sept 2017 at David Lays auction in Penzance, England – see Figure 8 below.

Figure 8

Briefly, it can be seen that this set also has ‘Rowbotham’ features and while broadly similar to sets in Figures 5 and 6 above, it has less angular, more bulbous stems and the kings have tiny frill design to their ball finials. The bulbous stems on the pawns seem to match more closely those of the pawns in the Windsor painting.

It is worth comparing this set (Fig. 8) with P141, an 18th century set on our site www.chessantiquesonline.com/rochford_collection/Eng_Playing_Sets.html - while both sets are broadly similar, P141, unlike Fig. 8, has a typical 18thC. castle as the rook and this shows how change in chess set design can be fluid and evolve over a period of time during which change can be in incremental

Interestingly, the sets in Figures 6 and 8 were both sourced from the southwest of England, raising the possibility of a regional connection to this design!

Conclusion

Hopefully these latest finds can put ‘flesh on the bones’ of the information about 16thC chess sets which could be gleaned from the material discussed at the beginning of this article and as a result bring us closer to having a better understanding of what English 16thC. chess sets looked like. There may be other examples of similar sets in collections and maybe this article will lead to further evidence being uncovered and presented in the future, which can help establish an even clearer picture of the chess sets that were in play at the time Rowbotham wrote his book and the Windsor family had their portraits painted while playing a game of chess some 450 years ago.

---------------------------------------

My thanks to Michael Mark for letting me use his already published material and indeed his incisive observations and feedback on this article.

Likewise, I very much appreciated Sir Alan Fersht’s consent to use the image of his early set and the helpful inputs I received from fellow collector Peter Armit.

Addendum A

Early English Chess Set with ‘Rowbotham’, features please see

www.chessantiquesonline.com/rochford_collection/Eng_Playing_Sets.html

(Set titled P153)

This is an early English turned fruitwood monobloc stained chess set - probably c. 1700. K. 8cms.

In design and construction, it is unusually complex and sophisticated, encompassing many different chess set design features across the pieces and having quality wood turning workmanship.

King(s)

The king has a tall waisted base capped by an inverted ring and surmounted by two circular flat knops, each decorated with fine tiered grooving and separated by a diamond cut baluster knop. The piece is topped by a waisted baluster knop with collar and plain ball finial.

Queen(s)

The queen is smaller but broadly similar in design to the king minus the baluster diamond knop.

Bishop(s)

The bishop has a domed base with inverted baluster ring above which there is a tapering cylindrical urn with surface banding and double collars surmounted by a bulbous split mitre.

Knight(s)

The knight has a domed base with an inverted ring under an onion baluster knop surmounted by a sliced circular top with incised lined banding and polished front.

Rook(s)

The rook is on a raised dome base with inverted ring and above which is a waisted baluster knop and topped by a wide and deep collar or knop with embedded plain ball finial.

Pawn(s)

The pawn is basically a smaller version of the rook but with regular collar and ball finial.

Note; In design terms, it is interesting to note that the rook and pawn are almost mirror images of the top portions of the king and queen and this provides symmetry and balance throughout the chess set.